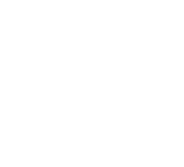

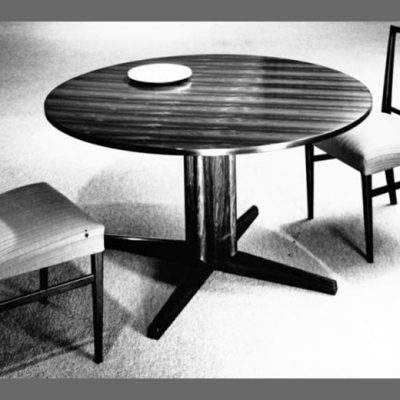

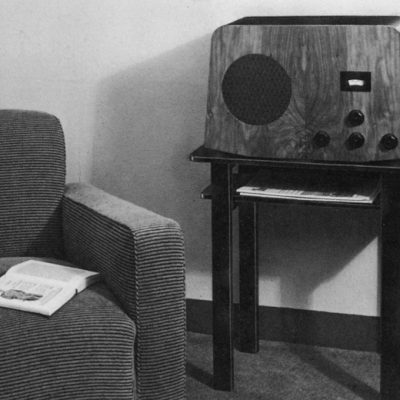

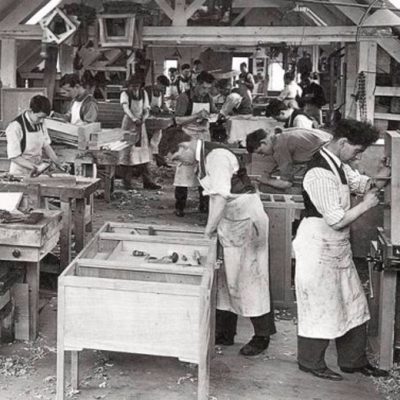

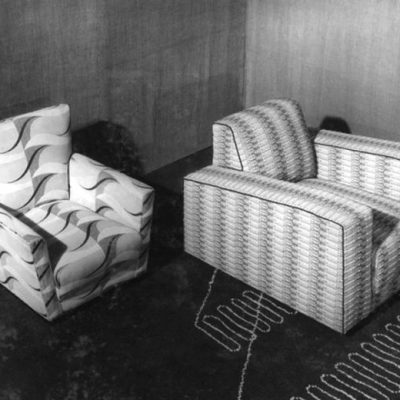

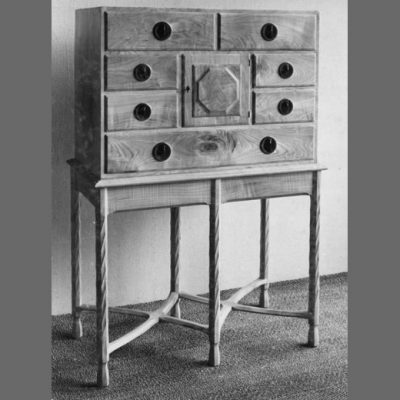

ARTS & CRAFTS TO MODERNISM

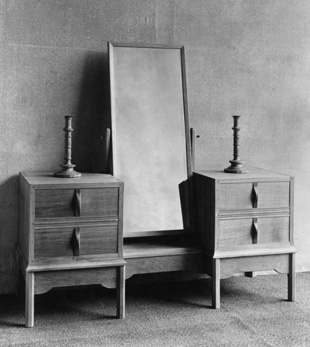

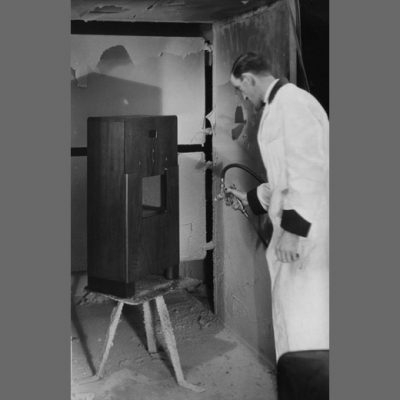

How Gordon Russell’s interest in the highest standards of furniture production enabled his company to encompass the span of 20th Century design. From his own early delight in the ideals held by the Arts and Crafts Movement through to cutting edge designs of later decades of the century. Commentary is provided by Jeremy Myerson, Luke Hughes and Ray Leigh.